사용자:NAKRI/연습장

중등 학교 중등학교(secondary school)란 중등 교육을 제공하는 학교로 만 11세에서 16세 또는 만 11세 에서 18세의 청소년들을 대상으로 하고 초등학교(primary school)의 교육 이후, 고등교육을 받기 이전의 교육을 담당한다.

국가별 현황[편집]

미국[편집]

미국에서는 secondary school이라는 용어가 여러 의미를 가질 수 있다. 고등학교(9학년 ~ 12학년)와 같은 학교를 의미할 수도 있고, 대안학교를 secondary school이라고 부르는 경우도 가끔 있다. 어떤 관할권 에서는 7학년에서 12학년까지의 학생들을 교육하는 기관 또는 중학교와 고등학교가 합쳐진, 예를 들어 버지니아 주의 "Robinson Secondary School" 같은 곳을 뜻하기도 한다.

캐나다[편집]

캐나다에서는 9학년에서 12학년(만 14~18세)의 학생들을 교육하는 학교를 의미한다. 변형되거나 세분된 학교들도 흔한데, 퀘벡 주 에서는 secondary1 ~ 5(7 ~ 11학년)학생들을 교육하는 기관이다.

| 이 글은 학교에 관한 토막글입니다. 여러분의 지식으로 알차게 문서를 완성해 갑시다. |

가속도 ,Acceleration[편집]

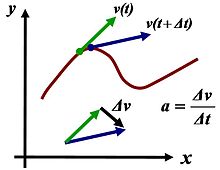

Accelerations are vector quantities (they have magnitude and direction) and add according to the parallelogram law.[2][3] As a vector, the calculated net force is equal to the product of the object's mass (a scalar quantity) and the acceleration. 가속도는 벡터이고 평행사변형법을 따른다. 벡터로써, 계산된 알짜힘은 물체의 질량(스칼라)과 가속도와 같다. 예를 들어 , 자동차가 정지된 상태에서 직선방향으로 속도를 높여 운동하게 되면 그것은 운동방향으로의 가속이다. 만약 자동차가 회전한다면 새로운 방향으로의 가속도가 생긴다.자동차가 앞으로 갈때는 자동차 안에있는 사람이 뒤로 밀리는 힘을 받고. 방향을 바꿀때, 자동차 안에 있는 사람은 옆으로 힘을 받는다. 만약 자동차의 속도가 감소한다면, 자동차에 반대방향으로의 가속도가 작용한다. 가끔씩 그것을 "감속도"라고 부른다. 탑승자는 앞으로 밀리는 힘을 받는다. For example, when a car starts from a standstill (zero relative velocity) and travels in a straight line at increasing speeds, it is accelerating in the direction of travel. If the car turns there is an acceleration toward the new direction. For this example, we can call the accelerating of the car forward a "linear acceleration", which passengers in the car might experience as force pushing them back into their seats. When changing directions, we might call this "non-linear acceleration", which passengers might experience as a sideways force. If the speed of the car decreases, this is an acceleration in the opposite direction of the direction of the vehicle, sometimes called deceleration.[1] Passengers may experience deceleration as a force lifting them away from their seats.

수학적으로, 감속도를 위한 공식은 존재하지 않는다. 속도가 빨라짐에 따라 각각의 가속도들(선형,비선형,감속)은 아마 승객들이 그들의 자와 맞는 방향과 속도로 느낄것이다. Mathematically, there is no separate formula for deceleration, as both are changes in velocity. Each of these accelerations (linear, non-linear, deceleration) might be felt by passengers until their velocity and direction match that of the car.

Definition and properties[편집]

수학적으로 즉각적인 가속은 극미한 간격의 시간동안의 속도 변화율을 의미한다. Mathematically, instantaneous acceleration—acceleration over an infinitesimal interval of time—is the rate of change of velocity over time:

- i.e., the derivative of the velocity vector as a function of time.

(Here and elsewhere, if motion is in a straight line, vector quantities can be substituted by scalars in the equations.) 어떤 시간동안의 평균 가속도는 다음과 같다. Average acceleration over a period of time is the change in velocity divided by the duration of the period

Acceleration has the dimensions of velocity (L/T) divided by time, i.e., L/T2. The SI unit of acceleration is the metre per second squared (m/s2); this can be called more meaningfully "metre per second per second", as the velocity in metres per second changes by the acceleration value, every second.

An object moving in a circular motion—such as a satellite orbiting the earth—is accelerating due to the change of direction of motion, although the magnitude (speed) may be constant. When an object is executing such a motion where it changes direction, but not speed, it is said to be undergoing centripetal (directed towards the center) acceleration. Oppositely, a change in the speed of an object, but not its direction of motion, is a tangential acceleration.

Proper acceleration, the acceleration of a body relative to a free-fall condition, is measured by an instrument called an accelerometer.

In classical mechanics, for a body with constant mass, the (vector) acceleration of the body's center of mass is proportional to the net force vector (i.e., sum of all forces) acting on it (Newton's second law):

where F is the net force acting on the body, m is the mass of the body, and a is the center-of-mass acceleration. As speeds approach the speed of light, relativistic effects become increasingly large and acceleration becomes less.

Tangential and centripetal acceleration[편집]

The velocity of a particle moving on a curved path as a function of time can be written as:

with v(t) equal to the speed of travel along the path, and

a unit vector tangent to the path pointing in the direction of motion at the chosen moment in time. Taking into account both the changing speed v(t) and the changing direction of ut, the acceleration of a particle moving on a curved path can be written using the chain rule of differentiation[2] for the product of two functions of time as:

where un is the unit (inward) normal vector to the particle's trajectory (also called the principal normal), and r is its instantaneous radius of curvature based upon the osculating circle at time t. These components are called the tangential acceleration and the normal or radial acceleration (or centripetal acceleration in circular motion, see also circular motion and centripetal force).

Geometrical analysis of three-dimensional space curves, which explains tangent, (principal) normal and binormal, is described by the Frenet–Serret formulas.[3][4]

- ↑ Raymond A. Serway, Chris Vuille, Jerry S. Faughn (2008). 《College Physics, Volume 10》. Cengage. 32쪽. ISBN 9780495386933.

- ↑ “Chain Rule”.

- ↑ Larry C. Andrews & Ronald L. Phillips (2003). 《Mathematical Techniques for Engineers and Scientists》. SPIE Press. 164쪽. ISBN 0-8194-4506-1.

- ↑ Ch V Ramana Murthy & NC Srinivas (2001). 《Applied Mathematics》. New Delhi: S. Chand & Co. 337쪽. ISBN 81-219-2082-5.